Personally, I think it works on a number of different levels - not that it's necessary to get into lots of analysis. But it made me smile, and I hope it does for all of you!

Translate

Saturday 30 June 2012

Who doesn't love Mr Darcy?

Just a little extra-curricular post - ostensibly, I'm working. However, one of my friends posted this on Facebook last night, and it tickled my funnybone. For general amusement, and comments if any of you so please, I give you Mr Darcy:

Personally, I think it works on a number of different levels - not that it's necessary to get into lots of analysis. But it made me smile, and I hope it does for all of you!

Personally, I think it works on a number of different levels - not that it's necessary to get into lots of analysis. But it made me smile, and I hope it does for all of you!

Friday 29 June 2012

Shakespeare's world portrayed by others

One of my fellow book bloggers, Peter, has been reading Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew for an upcoming book club meeting. First off, he had to go get himself a copy of the play, and agonised about whether to get it in the original, or one of the many versions created especially for study purposes. In the end, he bought one of each - the latter being a contemporary 'translation' of the original Elizabethan English. You can read his post and the accompanying comments here.

As any of my regular readers will be well aware, my brain is a madly tangental beast, and while I'm currently embroiled in a couple of different Shakespeare plays, courtesy of my students, Peter's post didn't send me straight to Shakespeare, but more to the issues of reading him, and the discussions people have as a result. I'm working with sixteen year old boys and to date, we've covered Macbeth, King Henry, and Othello. My kids did Richard the Third and Macbeth. I often wonder why it's mostly the histories that are used as school texts when the comedies are so accessible - and that's coming more from the point of being someone who does read and enjoy Shakespeare plays. I had the good fortune to be taught by a lover of the Bard when I was at school, and she was able to imbue in me - if not the others in my classes - a love of the language, rather than the fear and loathing that seems to be so much part of many people's high school experiences. I've also been lucky enough to see a good many very clever live productions. The more recent movie versions of many of the plays have much to recommend them as well. In addition to that, because of my singing background, I've sung in two of the three Shakespeare-based Verdi operas and have seen the third - Otello, Macbeth and Falstaff respectively (the latter being based on The Merry Wives of Windsor).

However, it was two things that really got me hooked on the plays - firstly, the comedies, none of which I'd read (although I've rectified that since), so my first exposure to them was in the theatre. I saw, in close succession, A Midsummer Night's Dream and Twelfth Night as modern productions and was both entranced and in stitches - particularly with Twelfth Night. I saw a wonderful production of The Taming of the Shrew in Canberra with a company of all male actors, as in Shakespeare's day, so the female parts were all in drag and it was just priceless. When I sang in Macbeth, it was on the school syllabus, so the opera company collaborated with a local theatre company to do a combined schools production on our set. We did bits of the opera - which was a very traditional setting - while the theatre company created a kind of Reader's Digest version of the entire play with mixed gender casting and a very modern interpretation of costuming and style. I sang Third Witch, and I'll never forget arriving for the first full dress rehearsal with the two other opera witches and coming face to face with the three witches from the theatre company. We were drab, ragged 10th century crones with great wooden staffs, and they were mad psychedelic Disney crossed with Witches of Eastwick! I'm not sure which of us was more stunned - we thought they were amazing and they thought we were awesome!

The other layer to my Shakespeare experience is less straightforward, and I dare say, much more obscure, and probably not common to most of my readers - unless they're YA fans with a predilection for English boarding school books, AND have discovered Antonia Forest's Marlow books... This post is by way of introducing Antonia Forest, as I'm about to re-read the pair of historical novels that she wrote alongside the main series, and I know that when I've done that I'll end up re-reading the main series again, because I love them. Look carefully upon the covers, folks, because they are the one and only edition ever to go to print and getting hold of them was a protracted and expensive business!

They're set in Shakespeare's time, beginning in the English countryside with the central character, Nicholas (an ancestor of the family in the modern series), running away from his brother's home after being expelled from school. Picked up by Kit Marlowe (a contemporary of Shakespeare's) who offers to pass him off as a cousin, he is whisked away in the night. As things come to pass, Kit is killed in a drunken brawl, and Nicholas is conveyed to London by Robin Poley, who drops him at the walls of the estate of the Earl of Southampton - Kit Marlowe's patron - to convey the news of Kit's death. However, Poley is a government spy and blackmails Nicholas, telling him he is to communicate anything 'useful' to the government's cause to him, or risk his life... When Nicholas is offered a place in the Earl's household, where he has been met with kindness, he refuses, knowing that he represents a threat to them and himself if he remains there. In due course, having discovered the boy possesses both a fine voice and a prodigious ability to memorise anything on one sighting, the Earl finds him a place with his other poet...the other poet being none other than Will Shakespeare.

The books cover a period of turbulent politics, during which the theatres were controlled by the government and plays were heavily vetted for possible treasonable content prior to being played. It includes the building of the Globe Theatre, and creates a wonderfully rich, beautifully researched - although fictionalised - account of the life of the company behind the plays. If you've read any histories of London of that time, you will recognise the scholarship in Forest's research. They are a wonderful read - for children and adults alike. This is one of the stand out features of this entire series - the modern books as well. Forest is a writer with a rare talent for elegant, witty prose that is, beyond any other characteristic, entirely believable. She has an outstanding ability to write wonderfully pithy dialogue that never fails to engage me, and there are particular conversations between characters that, despite man, many readings, still make me laugh and prompt me to read them out loud to whoever is in the vicinity.

What she does with these two books, is bring Shakepeare's world alive and makes it real. The boys play the young women in his plays, and we get an inside look at the gender politics of the time that forbade women to appear on stage. Older women are played by the adults in the company. As it is a small group, people usually have to play more than one character in any given play - and you can just imagine Shakespeare pondering the logistics of characters exiting and entering as he wrote, having to take into account who was playing who and how long they'd have to change costumes in between. There is also the ever present issue of the boys themselves and how long Shakespeare had with any of them before their voices broke and they could no longer play women. This is also the time of Richard Burbage, the first to play any of Shakespeare's heroes, and revered in all the histories that mention him as the greatest actor of his time.

Part of the charm of these books for me is that, like the movie Shakespeare in Love, we are afforded, via the gifts of clever writers, a glimpse of how it might have been in Shakespeare's time. It brings to mind that quote I used in my previous post from one of John Wyndham's stories about time travel - wouldn't you just love the opportunity to see the premier of a Shakespeare play, in The Globe, on the day, with the Bard himself in the cast - because he was a player himself before he started writing his own plays? If it were possible, then there would be the choice to make of where to sit - would one want to be among the groundlings, below the stage but close to the action, or up in the stands with the well to do? All I know is that my readings and other experiences of the plays are now coloured by the images I carry from these books, and others that do similar things. However, these are about as good as it's possible to get...

As any of my regular readers will be well aware, my brain is a madly tangental beast, and while I'm currently embroiled in a couple of different Shakespeare plays, courtesy of my students, Peter's post didn't send me straight to Shakespeare, but more to the issues of reading him, and the discussions people have as a result. I'm working with sixteen year old boys and to date, we've covered Macbeth, King Henry, and Othello. My kids did Richard the Third and Macbeth. I often wonder why it's mostly the histories that are used as school texts when the comedies are so accessible - and that's coming more from the point of being someone who does read and enjoy Shakespeare plays. I had the good fortune to be taught by a lover of the Bard when I was at school, and she was able to imbue in me - if not the others in my classes - a love of the language, rather than the fear and loathing that seems to be so much part of many people's high school experiences. I've also been lucky enough to see a good many very clever live productions. The more recent movie versions of many of the plays have much to recommend them as well. In addition to that, because of my singing background, I've sung in two of the three Shakespeare-based Verdi operas and have seen the third - Otello, Macbeth and Falstaff respectively (the latter being based on The Merry Wives of Windsor).

However, it was two things that really got me hooked on the plays - firstly, the comedies, none of which I'd read (although I've rectified that since), so my first exposure to them was in the theatre. I saw, in close succession, A Midsummer Night's Dream and Twelfth Night as modern productions and was both entranced and in stitches - particularly with Twelfth Night. I saw a wonderful production of The Taming of the Shrew in Canberra with a company of all male actors, as in Shakespeare's day, so the female parts were all in drag and it was just priceless. When I sang in Macbeth, it was on the school syllabus, so the opera company collaborated with a local theatre company to do a combined schools production on our set. We did bits of the opera - which was a very traditional setting - while the theatre company created a kind of Reader's Digest version of the entire play with mixed gender casting and a very modern interpretation of costuming and style. I sang Third Witch, and I'll never forget arriving for the first full dress rehearsal with the two other opera witches and coming face to face with the three witches from the theatre company. We were drab, ragged 10th century crones with great wooden staffs, and they were mad psychedelic Disney crossed with Witches of Eastwick! I'm not sure which of us was more stunned - we thought they were amazing and they thought we were awesome!

The other layer to my Shakespeare experience is less straightforward, and I dare say, much more obscure, and probably not common to most of my readers - unless they're YA fans with a predilection for English boarding school books, AND have discovered Antonia Forest's Marlow books... This post is by way of introducing Antonia Forest, as I'm about to re-read the pair of historical novels that she wrote alongside the main series, and I know that when I've done that I'll end up re-reading the main series again, because I love them. Look carefully upon the covers, folks, because they are the one and only edition ever to go to print and getting hold of them was a protracted and expensive business!

They're set in Shakespeare's time, beginning in the English countryside with the central character, Nicholas (an ancestor of the family in the modern series), running away from his brother's home after being expelled from school. Picked up by Kit Marlowe (a contemporary of Shakespeare's) who offers to pass him off as a cousin, he is whisked away in the night. As things come to pass, Kit is killed in a drunken brawl, and Nicholas is conveyed to London by Robin Poley, who drops him at the walls of the estate of the Earl of Southampton - Kit Marlowe's patron - to convey the news of Kit's death. However, Poley is a government spy and blackmails Nicholas, telling him he is to communicate anything 'useful' to the government's cause to him, or risk his life... When Nicholas is offered a place in the Earl's household, where he has been met with kindness, he refuses, knowing that he represents a threat to them and himself if he remains there. In due course, having discovered the boy possesses both a fine voice and a prodigious ability to memorise anything on one sighting, the Earl finds him a place with his other poet...the other poet being none other than Will Shakespeare.

The books cover a period of turbulent politics, during which the theatres were controlled by the government and plays were heavily vetted for possible treasonable content prior to being played. It includes the building of the Globe Theatre, and creates a wonderfully rich, beautifully researched - although fictionalised - account of the life of the company behind the plays. If you've read any histories of London of that time, you will recognise the scholarship in Forest's research. They are a wonderful read - for children and adults alike. This is one of the stand out features of this entire series - the modern books as well. Forest is a writer with a rare talent for elegant, witty prose that is, beyond any other characteristic, entirely believable. She has an outstanding ability to write wonderfully pithy dialogue that never fails to engage me, and there are particular conversations between characters that, despite man, many readings, still make me laugh and prompt me to read them out loud to whoever is in the vicinity.

What she does with these two books, is bring Shakepeare's world alive and makes it real. The boys play the young women in his plays, and we get an inside look at the gender politics of the time that forbade women to appear on stage. Older women are played by the adults in the company. As it is a small group, people usually have to play more than one character in any given play - and you can just imagine Shakespeare pondering the logistics of characters exiting and entering as he wrote, having to take into account who was playing who and how long they'd have to change costumes in between. There is also the ever present issue of the boys themselves and how long Shakespeare had with any of them before their voices broke and they could no longer play women. This is also the time of Richard Burbage, the first to play any of Shakespeare's heroes, and revered in all the histories that mention him as the greatest actor of his time.

Part of the charm of these books for me is that, like the movie Shakespeare in Love, we are afforded, via the gifts of clever writers, a glimpse of how it might have been in Shakespeare's time. It brings to mind that quote I used in my previous post from one of John Wyndham's stories about time travel - wouldn't you just love the opportunity to see the premier of a Shakespeare play, in The Globe, on the day, with the Bard himself in the cast - because he was a player himself before he started writing his own plays? If it were possible, then there would be the choice to make of where to sit - would one want to be among the groundlings, below the stage but close to the action, or up in the stands with the well to do? All I know is that my readings and other experiences of the plays are now coloured by the images I carry from these books, and others that do similar things. However, these are about as good as it's possible to get...

Thursday 28 June 2012

Book junkie heaven...

...well, a little slice of book junkie heaven! Finally, I made it to the post office box and in amongst the boring, windowed envelopes was a small padded bag with a handwritten address containing THIS! Peter, over at Kyusireader, eat your heart out...just look at my new treasure... As I said, after some hunting around eBay, I came across this copy of John Wyndham's The Seeds of Time, the anthology I've been missing for ages, and bought it. It's a 1962 Penguin edition with, huge bonus, a two page foreword by the man himself discussing the science fiction genre and positioning himself within it with this collection of short stories. They were written over a fifteen year period and he refers to them as 'experiments' with the genre, which opened up when,

Having collected my parcel and gloated over the contents briefly, I decided that the next bit of my morning could wait just a little while - long enough for me to read just one story - hence the accompanying photo! I started at the beginning with the first story, Chronoclasm, which deals with time travel and the potential consequences of interfering with history. The feelings that I think we all nurse about time travel are summed up beautiful by Tavia, the female lead, who has come to 1950s Britain from the twenty-second century,

Now I have to get on with my work for the day, but there are eight more stories to go yet....including the chilling Survival, which is the one I have the clearest memories of...again, another hanging ending, but with a very nasty twist.

...there came a time when certain editors [of magazines] grew mildly mutinous with the perception that the terms of reference did not truly restrict them to the adventures of galactic gangsters in space-opera, and they began, some by stealth, some by declaration, to encourage their authors to do a bit more exploration within the definition.Wyndham wraps up his foreword by thanking numerous un-met editors who, as he says '...encouraged me by printing one or more of these experiments on the theme: 'I wonder what might happen if...?'' Thank goodness they did, or we might not have his wonderful novels.

Having collected my parcel and gloated over the contents briefly, I decided that the next bit of my morning could wait just a little while - long enough for me to read just one story - hence the accompanying photo! I started at the beginning with the first story, Chronoclasm, which deals with time travel and the potential consequences of interfering with history. The feelings that I think we all nurse about time travel are summed up beautiful by Tavia, the female lead, who has come to 1950s Britain from the twenty-second century,

...all the things one could do! Fancy being at the first night of a new Shaw play, or a new Coward play, in a real theatre! Or getting a brand-new T.S. Eliot on publishing day. Or seeing the Queen drive by to open Parliament. A wonderful, thrilling time!It's a delightful, bittersweet story that leaves the reader hanging at the end, wishing there was more - that tantilising thing about short stories! I got all my errands done and came home to crash with tea and the second story, Time to Rest. It's a different beast; the story of the remnants of the human race, all men, marooned on Mars following the end of Earth's existence. The central character, Bert, was on the last ship that left Earth, and with his fellow crew watched the Earth split open and self destruct. By a mixture of guess work and navigation through a changing space, they make it to Mars, where they're slowly joined by others coming back from different exploratory journeys, to end their days on the red planet. It's a sombre, bleak little story - one that I don't think I'd manage if it were a full length book.

Now I have to get on with my work for the day, but there are eight more stories to go yet....including the chilling Survival, which is the one I have the clearest memories of...again, another hanging ending, but with a very nasty twist.

Monday 25 June 2012

Beyond Chocolat

The joy of finding a new author to explore is never to be underestimated. I had a conversation recently with my BFF about Joanne Harris' books in the wake of my haphazard acquisition of the Chocolat trilogy, and she'd bought the latest of the three on the basis of it being written by Harris without being particularly aware of the connection - because she's bought all of Harris' books since Chocolat. And here's me just discovering them! That's OK, we've had similar conversations in reverse - one of them in the last few weeks actually, because somehow L.M. Montgomery's 'Anne' books had eluded her until now, so she's been on a voyage of discovery with those.

I loved Chocolat - as I said in my post about it, which you can read here if you haven't already. Apart from the fact that Harris is a writer with a wonderful talent for telling a story, there is a glorious element of play. It gives the book, despite some of the darker elements, a sense of innocence at times that is most beguiling. Moving onto the next stage of Vianne and Anouk's lives, that innocence is absent.

Lollipop Shoes takes place four years in Paris, after they leave Lasquenet. They have, once again, changed their names, Vianne is Yanne, and Anouk has become Annie. They have become three, with the birth of Rosette, Roux's daughter - although, that is not information Vianne has shared with anyone. The events surrounding their flight from Lasquenet, Rosette's birth, and subsequent arrival in Paris are hinted at, little bits here and there, enough to tantalise but not to make clear why it is that Vianne is just barely scraping a living in a tiny patisserie in Montmartre, Anouk is distant with gathering adolescent storm clouds and there is none of the lighthearted staring down of life's challenges that characterised them in Chocolat.

Instead of living the truth they lived before Rosette's birth, Vianne is trying to create a life that is 'normal'. Rosette was a sickly baby who did not thrive. Even now, she is much smaller than usual for her almost four years and she doesn't speak. She does however, have an imaginary friend, Bam, as Anouk did with Pantoufle. We find Vianne and the girls at a turning point. Their landlady, and partner in the business, has just died. The owner of the building, Thierry, is away on business can can't be at the funeral, but sends a message to say that they're not to worry, something can be worked out. At the same time, a mysterious stranger arrives, Zozie de l'Alba - quirky, loud, confident, charming and, above all, helpful.

This is indicative of the tone of this book - everything feels as if it's a back story. There was a direct quality to the story-telling in Chocolat. Lollipop Shoes is full of hidden messages, secrets, half-truths, and layers of mystery. No-one is quite what they appear to be - we know that Vianne is not being herself, and as a result, Anouk is being stifled. Thierry appears to be the consummate good guy, helpful when things need to be done and outwardly supportive of Vianne and the girls - in reality, he is a control freak; someone who, as long as he is in charge, can be magnanimous and caring. Zozie, who arrives on the wind - something Vianne is aware of but refuses to acknowledge - has an agenda, and her story emerges as a parallel narrative. Piece by piece, almost sitting in the same position as Vianne, we are allowed in to see Zozie's subtle, clever invasion of Vianne's little family, motivated by her desire to get hold of Anouk, Anouk who has great powers, although they are being stifled, like Vianne's, due to fear. Zozie encourages Vianne to go back to making chocolate, instead of the basic patisserie fare she's been struggling to make financially viable and slowly, the magic begins to have its effect on the surrounding community as it did back in Lasquenet.

When Roux arrives unexpectedly in Paris, Vianne's composure and careful construct is shattered. Unbeknown to her, he had sent a postcard to let her know he was coming - a postcard appropriated by Zozie. Now, in the mix of people working hard to preserve various facades, there are two who don't - because they can't - Roux and small Rosette.

There is darkness and real evil in this book, and for the first time, the nature of the magic that was just an undercurrent in Chocolat is spelled out. Zozie represents all that can be misused with witchcraft, while Vianne, Anouk and Rosette are crafted from very different cloth. Ultimately, the climax of the novel is an elemental struggle of good and evil, with some unexpected results.

Peaches for Monsieur le Cure takes us four years on again - I don't know if this was planned or not. Vianne, having reverted to her original name, and the girls are living with Roux on a houseboat moored on the Siene, still in Paris. Roux has built for them a compromise - from the houseboat, Vianne runs a small chocolaterie, Roux picks up odd jobs, Anouk is in school and Rosette is her inimitable, individual self - still not speaking much, but seeing... And then comes a letter from the dead - a letter from Armande, via her grandson Luc, telling her to return to Lasquenet, to pick the peaches from Armande's tree, to bring the girls, that there is a need for her in the village.

Lasquenet has changed, as have many areas of France, and this was a totally unexpected aspect of this third book. There is an air of the fairy-tale about these books, steeped as they are in magic and mystery, and to have that fairy-tale colour juxtaposed against the edgy politics of current multicultural issues in Europe was a bit jarring at first. Perhaps it's that while we see many of these issues played out in the news in big cities, we don't often get a picture of how the impact of the growth of Muslim communities within smaller towns and villages has been and continues to be.

Tensions in the village have grown way beyond those that Vianne experienced during her first time there. The Muslim community has grown, with many more people arriving from Tangier, and a mosque has been established in one of the old buildings. There are enormous tensions between the old villagers and the new community - but also, on each side of that schism, there are issues within the original village community, and within the Muslim community. In both, the original religious leaders are being usurped by younger, 'more progressive' men, and both the older leaders appear to be crumbling before the onslaught. People's perceptions of rights and wrongs within their own groups and across the cultural divide are being coloured by deeply held prejudices and fears. Vianne finds that while some people welcome her back, others view her with deep suspicion. She begins to question why she came, why she took Armande's letter so to heart, and why she ever thought she could do anything for anyone. It is the same insecurities that wracked her in Lollipop Shoes, reawakened when it seems that her powers are required, and those of her children are coming alive again in an environment they both love.

In one poignant paragraph, everything she has ever wanted but never allowed herself to acknowledge or - more importantly - really have, is summed up so perfectly. Well, I thought it was, but perhaps that speaks of my own yearnings, unwilling gypsy child that I am:

There are many small and large dramas played out in the narrative. She is involved in some directly, in others she is the catalyst, and in some she is more of a bystander. But they all touch her, and they all contribute to her understanding of herself.

These are exquisitely written books. I have been quite unwell for some weeks, and this past weekend was spent mostly on the couch. It was timely, perhaps, that I had new books, but I have to say, these weren't just any new books. As I said at the beginning of this post, finding a new author is something special. I have a whole new treasure chest of stories awaiting me from Joanne Harris, and if you've never read any of her books, I suggest you get ye hence to your local bookstore and add them to your collection!

I loved Chocolat - as I said in my post about it, which you can read here if you haven't already. Apart from the fact that Harris is a writer with a wonderful talent for telling a story, there is a glorious element of play. It gives the book, despite some of the darker elements, a sense of innocence at times that is most beguiling. Moving onto the next stage of Vianne and Anouk's lives, that innocence is absent.

Lollipop Shoes takes place four years in Paris, after they leave Lasquenet. They have, once again, changed their names, Vianne is Yanne, and Anouk has become Annie. They have become three, with the birth of Rosette, Roux's daughter - although, that is not information Vianne has shared with anyone. The events surrounding their flight from Lasquenet, Rosette's birth, and subsequent arrival in Paris are hinted at, little bits here and there, enough to tantalise but not to make clear why it is that Vianne is just barely scraping a living in a tiny patisserie in Montmartre, Anouk is distant with gathering adolescent storm clouds and there is none of the lighthearted staring down of life's challenges that characterised them in Chocolat.

Instead of living the truth they lived before Rosette's birth, Vianne is trying to create a life that is 'normal'. Rosette was a sickly baby who did not thrive. Even now, she is much smaller than usual for her almost four years and she doesn't speak. She does however, have an imaginary friend, Bam, as Anouk did with Pantoufle. We find Vianne and the girls at a turning point. Their landlady, and partner in the business, has just died. The owner of the building, Thierry, is away on business can can't be at the funeral, but sends a message to say that they're not to worry, something can be worked out. At the same time, a mysterious stranger arrives, Zozie de l'Alba - quirky, loud, confident, charming and, above all, helpful.

This is indicative of the tone of this book - everything feels as if it's a back story. There was a direct quality to the story-telling in Chocolat. Lollipop Shoes is full of hidden messages, secrets, half-truths, and layers of mystery. No-one is quite what they appear to be - we know that Vianne is not being herself, and as a result, Anouk is being stifled. Thierry appears to be the consummate good guy, helpful when things need to be done and outwardly supportive of Vianne and the girls - in reality, he is a control freak; someone who, as long as he is in charge, can be magnanimous and caring. Zozie, who arrives on the wind - something Vianne is aware of but refuses to acknowledge - has an agenda, and her story emerges as a parallel narrative. Piece by piece, almost sitting in the same position as Vianne, we are allowed in to see Zozie's subtle, clever invasion of Vianne's little family, motivated by her desire to get hold of Anouk, Anouk who has great powers, although they are being stifled, like Vianne's, due to fear. Zozie encourages Vianne to go back to making chocolate, instead of the basic patisserie fare she's been struggling to make financially viable and slowly, the magic begins to have its effect on the surrounding community as it did back in Lasquenet.

When Roux arrives unexpectedly in Paris, Vianne's composure and careful construct is shattered. Unbeknown to her, he had sent a postcard to let her know he was coming - a postcard appropriated by Zozie. Now, in the mix of people working hard to preserve various facades, there are two who don't - because they can't - Roux and small Rosette.

There is darkness and real evil in this book, and for the first time, the nature of the magic that was just an undercurrent in Chocolat is spelled out. Zozie represents all that can be misused with witchcraft, while Vianne, Anouk and Rosette are crafted from very different cloth. Ultimately, the climax of the novel is an elemental struggle of good and evil, with some unexpected results.

Peaches for Monsieur le Cure takes us four years on again - I don't know if this was planned or not. Vianne, having reverted to her original name, and the girls are living with Roux on a houseboat moored on the Siene, still in Paris. Roux has built for them a compromise - from the houseboat, Vianne runs a small chocolaterie, Roux picks up odd jobs, Anouk is in school and Rosette is her inimitable, individual self - still not speaking much, but seeing... And then comes a letter from the dead - a letter from Armande, via her grandson Luc, telling her to return to Lasquenet, to pick the peaches from Armande's tree, to bring the girls, that there is a need for her in the village.

Lasquenet has changed, as have many areas of France, and this was a totally unexpected aspect of this third book. There is an air of the fairy-tale about these books, steeped as they are in magic and mystery, and to have that fairy-tale colour juxtaposed against the edgy politics of current multicultural issues in Europe was a bit jarring at first. Perhaps it's that while we see many of these issues played out in the news in big cities, we don't often get a picture of how the impact of the growth of Muslim communities within smaller towns and villages has been and continues to be.

In one poignant paragraph, everything she has ever wanted but never allowed herself to acknowledge or - more importantly - really have, is summed up so perfectly. Well, I thought it was, but perhaps that speaks of my own yearnings, unwilling gypsy child that I am:

There's something very comforting about the ritual of jam-making. It speaks of cellars filled with preserves; of neat rows of jars on pantry shelves. It speaks of winter mornings and bowls of choclat au lait, with thick slices of food fresh bread and last year's peach jam, like a promise of sunshine at the darkest point of the year. It speaks of four stone walls, a roof, and of seasons that turn in the same place, in the same way, year after year, with sweet familiarity. It is the taste of home.Ultimately, Vianne's journey back to Lasquenet is a means of coming to terms with herself, with who she is, with what she is. It is a means of coming to an acceptance of what her children have inherited and that she must allow them to be who they are. It is when she learns that she needs to be able to trust the people close to her, and let them in.

There are many small and large dramas played out in the narrative. She is involved in some directly, in others she is the catalyst, and in some she is more of a bystander. But they all touch her, and they all contribute to her understanding of herself.

These are exquisitely written books. I have been quite unwell for some weeks, and this past weekend was spent mostly on the couch. It was timely, perhaps, that I had new books, but I have to say, these weren't just any new books. As I said at the beginning of this post, finding a new author is something special. I have a whole new treasure chest of stories awaiting me from Joanne Harris, and if you've never read any of her books, I suggest you get ye hence to your local bookstore and add them to your collection!

Thursday 21 June 2012

Who will inherit your books?

I came across an article this morning, courtesy of another blog I follow - look here - that spoke of something that I'm sure all of us who create libraries consider at some point when we think on these things that none of us really want to think about... What will happen to these treasured collections when we are no longer here to enjoy them? Amanda Katz's article, Will your children inherit your eBooks? looks at many of the issues I've been exploring from time to time in various posts, about the nature of actual books and the changing ways we read.

She suggests that the books themselves in any particular collection will dictate, to a certain extent, what happens to them. Books of value will stand more chance of being kept, or at least sold on to someone else who will keep them. A lot of popular fiction has, in all likelihood, a much more tenuous chance of being kept and treasured.

I remember my kids discussing the fate of my books with me once. It was mildly amusing. Twenty Seven was wandering the shelves, identifying various volumes that he knew were 'collectibles' and were, therefore, valuable - and put his name down for those. Twenty One had a more eclectic approach, picking out particular series that he had a liking for, without paying much attention to what they might be worth. He laid claim to all my Arthur Ransomes, on the basis that the dust-jacketed copy of Swallows and Amazons is actually his - my mother gave it to him years ago and he asked to keep in in my shelves - and I collected the rest of them. His logic was that there wasn't much point in Twenty Seven having them if he didn't have the first one.

Katz wrote about the rise of the eBook and the somewhat dubious joys of inheriting someone's kindle... Or being able to access, in perpetuity via the Cloud, someone's annotations in their electronic reading material. Apparently, new technology now allows Kindle readers to share their annotations with anyone who's reading the same book - I don't like reading highlighted texts at the best of times, so the mind boggles at what that experience could be like! Personally - as will come as no surprise to any of my regular readers - this holds absolutely no appeal for me at all.

I have a particular memory of Twenty One as a wee thing - actually, many memories, because this was a repeated activity. At an age where I should have been able to hear him constantly all over the house, I would become aware that it had been quiet for some time - a warning for any parent of small children... On checking out his bedroom, I would find him quietly engrossed in creating an entire world on his floor. All the matchbox cars would be out, all the Duplo and Lego would have been made into buildings of various sizes. The smaller of his 'people' (stuffed toys) populated this world and the streets were paved with...books. Every book in his own bookcase, some 'borrowed' from his brother's, and if he'd run short there'd have been an incursion into mine, had been laid down to create the roads. The fact that they were all different sizes and thicknesses didn't appear to be an issue, and he wasn't walking on them himself - he was very carefully edging around on the miniscule bits of floor he had left to keep everyone in his new world occupied.

I tell this story because it couldn't have happened without a house full of books being at his disposal. The end of these worlds involved - as you can imagine - lots of packing up. That was a long, drawn out affair when it came to dismantling the roads, because he needed help putting all the books back in the right places, which meant looking at them, which meant in some cases, stopping to read them together.

I like to think of my books being something that doesn't represent an awful problem for them when I'm dead. I'd like to think that they'll meet and pack them up together, divide them amongst themselves and their families if they have them, and pass them on for other children to read and build roads with. There are some valuable collector's items in my collection, but they're there because they're books I love and read. Over the years, there have been many times I've been urged to sell them when money has been tight, and if I'd only bought them for their dollar value, perhaps I'd have considered it at times. But I didn't. I bought them because of what's inside them - a magic that is priceless.

For Twenty One, because he follows this blog, this picture in memory of those worlds, and because with a collection as big as mine, and as big as some of my fellow book junkies who also read me, you could do this, if you felt so inclined. I feel kind of sad for the eBook readers, because you can't do this with a single Kindle or tablet!

She suggests that the books themselves in any particular collection will dictate, to a certain extent, what happens to them. Books of value will stand more chance of being kept, or at least sold on to someone else who will keep them. A lot of popular fiction has, in all likelihood, a much more tenuous chance of being kept and treasured.

I remember my kids discussing the fate of my books with me once. It was mildly amusing. Twenty Seven was wandering the shelves, identifying various volumes that he knew were 'collectibles' and were, therefore, valuable - and put his name down for those. Twenty One had a more eclectic approach, picking out particular series that he had a liking for, without paying much attention to what they might be worth. He laid claim to all my Arthur Ransomes, on the basis that the dust-jacketed copy of Swallows and Amazons is actually his - my mother gave it to him years ago and he asked to keep in in my shelves - and I collected the rest of them. His logic was that there wasn't much point in Twenty Seven having them if he didn't have the first one.

Katz wrote about the rise of the eBook and the somewhat dubious joys of inheriting someone's kindle... Or being able to access, in perpetuity via the Cloud, someone's annotations in their electronic reading material. Apparently, new technology now allows Kindle readers to share their annotations with anyone who's reading the same book - I don't like reading highlighted texts at the best of times, so the mind boggles at what that experience could be like! Personally - as will come as no surprise to any of my regular readers - this holds absolutely no appeal for me at all.

I have a particular memory of Twenty One as a wee thing - actually, many memories, because this was a repeated activity. At an age where I should have been able to hear him constantly all over the house, I would become aware that it had been quiet for some time - a warning for any parent of small children... On checking out his bedroom, I would find him quietly engrossed in creating an entire world on his floor. All the matchbox cars would be out, all the Duplo and Lego would have been made into buildings of various sizes. The smaller of his 'people' (stuffed toys) populated this world and the streets were paved with...books. Every book in his own bookcase, some 'borrowed' from his brother's, and if he'd run short there'd have been an incursion into mine, had been laid down to create the roads. The fact that they were all different sizes and thicknesses didn't appear to be an issue, and he wasn't walking on them himself - he was very carefully edging around on the miniscule bits of floor he had left to keep everyone in his new world occupied.

I tell this story because it couldn't have happened without a house full of books being at his disposal. The end of these worlds involved - as you can imagine - lots of packing up. That was a long, drawn out affair when it came to dismantling the roads, because he needed help putting all the books back in the right places, which meant looking at them, which meant in some cases, stopping to read them together.

I like to think of my books being something that doesn't represent an awful problem for them when I'm dead. I'd like to think that they'll meet and pack them up together, divide them amongst themselves and their families if they have them, and pass them on for other children to read and build roads with. There are some valuable collector's items in my collection, but they're there because they're books I love and read. Over the years, there have been many times I've been urged to sell them when money has been tight, and if I'd only bought them for their dollar value, perhaps I'd have considered it at times. But I didn't. I bought them because of what's inside them - a magic that is priceless.

For Twenty One, because he follows this blog, this picture in memory of those worlds, and because with a collection as big as mine, and as big as some of my fellow book junkies who also read me, you could do this, if you felt so inclined. I feel kind of sad for the eBook readers, because you can't do this with a single Kindle or tablet!

Do follow the link and read Amanda Katz's article if you haven't already - the back story that prompted her writing of it is one of those lovely things. Do you have a story of a particular book that it brings to mind?

Wednesday 20 June 2012

What are books?

Funny kind of question, isn't it? But, how many times do you find yourself having one of those odd detached moments of looking at an item that you know well - an ordinary, everyday item - and seeing it suddenly with quite new eyes? I do this at odd moments - it can be quite random. I think, at some deep level, it's part of processing all the 'stuff' around me.

Dearly Beloved and I go and look at houses for sale. We're not about to purchase anything at the moment, it's more about giving ourselves something to aim for, an incentive to keep plugging away at our various endeavours. We have quite similar tastes in many things - but quite different ideas, often, about the amount of space we need. There's a book I must heave out of storage - there's a particular box in storage that was never meant to go there at all...and it's in that box. It's complex, so I'll leave the analysis for now, but there's a component in it about the excess space we have created for ourselves in the homes we build nowadays and the stuff we pack into that space rather than the space we need to have that is sufficient to shelter us. It's come back to haunt me due to seeing so many very large houses lately, and that's lead to this particular train of thought.

A friend of mine is writing a blog that looks at the footprint her family is leaving behind them - you can check it out here - and that's another part of my thinking. There's also the downsizing we've had to do in this recent move, and the editing of possessions. It comes down to a basic question, for me, that goes something along the lines of, "What is all this stuff, and do I really need it?" - and if the question becomes part of a general discussion, inevitably, my books come into it. It's not unreasonable, on a physical level.

As all of you know, moving books is a right pain. They're heavy. You can never put as many as you think will fit into a box that can still be picked up when it's full. So, a large collection can mean an inordinate number of boxes. Then there's where to put the bookcases - as I said to DB on the weekend when we were discussing one particular house (a smaller, really quirky one that I really fell in love with), I can find places for bookcases anywhere! I've had lots of practice, gypsy type that life has made of me... He laughed, and agreed with me. For me, it comes down to the books being something more than just heavy paper things to be carted from place to place. When I go into a house that's open for inspection and there are no books anywhere, there is an emptiness, regardless of how nice it might be, how well the spaces might work, or how well it's been decorated. Somehow, there is no soul in a house without books.

I have moved house, on average, about every two years my whole life. I hate moving. There are only a handful of moves in that multitude of upheavals that have been of my choice. Most of them were force of circumstances, or the needs of other people. Consequently, the books have been packed and unpacked, stacked and re-stacked, arranged and rearranged more times than I care to think about. Once, and once only, I lived in a house with a room that became the library. It had a fireplace, I sourced a small vintage couch from a secondhand shop, my piano was on one wall, and the other walls were covered in books - right to the ceiling on one of them - there were even books on the mantlepiece. Everywhere else, the books have been fitted wherever I could manage to fit the growing collection of bookcases necessary to contain them. For years I carted around a collection of besser bricks (breeze blocks) and pine planks that got rejigged into various configurations, depending on the available space.

DB is the only person who has ever packed and moved my books for me. As they grew, my kids helped - complaining loudly - in past moves. "Why can't you collect something light, like feathers???" The re-stacking has always been my job, because I have systems and patterns that I need to figure out so I can, once they're all in the bookcases, walk into the room with my eyes shut and put my hand on exactly the book I'm after without looking - and I really can do that!

Why do we do this? Committed book junkies never question this mad activity, this massive extra load that is part of moving house. Of course the books go. All of them. Only rarely - as is the case at the moment for me - do we consign books to storage. Other things, certainly, but not the books. And, I miss the ones that aren't on the bookcases here. I feel their absence.

Books aren't just things. While they may be beautiful objects in their own right, they are treasures. They are worlds into which we can escape, visions we can borrow and inhabit for a while before we rejoin our normal routines. They are also memories; the books themselves carry bits of the people we've shared them with received them from, read them to... Everyone's book collection is almost like some weird fusion of a portrait and a self-portrait. You can gain a lot of insights about a person by looking at their books.

To close this ruminative post, an image appropriated from a friend which sums it up in a very short phrase:

Dearly Beloved and I go and look at houses for sale. We're not about to purchase anything at the moment, it's more about giving ourselves something to aim for, an incentive to keep plugging away at our various endeavours. We have quite similar tastes in many things - but quite different ideas, often, about the amount of space we need. There's a book I must heave out of storage - there's a particular box in storage that was never meant to go there at all...and it's in that box. It's complex, so I'll leave the analysis for now, but there's a component in it about the excess space we have created for ourselves in the homes we build nowadays and the stuff we pack into that space rather than the space we need to have that is sufficient to shelter us. It's come back to haunt me due to seeing so many very large houses lately, and that's lead to this particular train of thought.

A friend of mine is writing a blog that looks at the footprint her family is leaving behind them - you can check it out here - and that's another part of my thinking. There's also the downsizing we've had to do in this recent move, and the editing of possessions. It comes down to a basic question, for me, that goes something along the lines of, "What is all this stuff, and do I really need it?" - and if the question becomes part of a general discussion, inevitably, my books come into it. It's not unreasonable, on a physical level.

As all of you know, moving books is a right pain. They're heavy. You can never put as many as you think will fit into a box that can still be picked up when it's full. So, a large collection can mean an inordinate number of boxes. Then there's where to put the bookcases - as I said to DB on the weekend when we were discussing one particular house (a smaller, really quirky one that I really fell in love with), I can find places for bookcases anywhere! I've had lots of practice, gypsy type that life has made of me... He laughed, and agreed with me. For me, it comes down to the books being something more than just heavy paper things to be carted from place to place. When I go into a house that's open for inspection and there are no books anywhere, there is an emptiness, regardless of how nice it might be, how well the spaces might work, or how well it's been decorated. Somehow, there is no soul in a house without books.

I have moved house, on average, about every two years my whole life. I hate moving. There are only a handful of moves in that multitude of upheavals that have been of my choice. Most of them were force of circumstances, or the needs of other people. Consequently, the books have been packed and unpacked, stacked and re-stacked, arranged and rearranged more times than I care to think about. Once, and once only, I lived in a house with a room that became the library. It had a fireplace, I sourced a small vintage couch from a secondhand shop, my piano was on one wall, and the other walls were covered in books - right to the ceiling on one of them - there were even books on the mantlepiece. Everywhere else, the books have been fitted wherever I could manage to fit the growing collection of bookcases necessary to contain them. For years I carted around a collection of besser bricks (breeze blocks) and pine planks that got rejigged into various configurations, depending on the available space.

DB is the only person who has ever packed and moved my books for me. As they grew, my kids helped - complaining loudly - in past moves. "Why can't you collect something light, like feathers???" The re-stacking has always been my job, because I have systems and patterns that I need to figure out so I can, once they're all in the bookcases, walk into the room with my eyes shut and put my hand on exactly the book I'm after without looking - and I really can do that!

Why do we do this? Committed book junkies never question this mad activity, this massive extra load that is part of moving house. Of course the books go. All of them. Only rarely - as is the case at the moment for me - do we consign books to storage. Other things, certainly, but not the books. And, I miss the ones that aren't on the bookcases here. I feel their absence.

Books aren't just things. While they may be beautiful objects in their own right, they are treasures. They are worlds into which we can escape, visions we can borrow and inhabit for a while before we rejoin our normal routines. They are also memories; the books themselves carry bits of the people we've shared them with received them from, read them to... Everyone's book collection is almost like some weird fusion of a portrait and a self-portrait. You can gain a lot of insights about a person by looking at their books.

To close this ruminative post, an image appropriated from a friend which sums it up in a very short phrase:

Tuesday 19 June 2012

Chocolat - Joanne Harris

I don't know how I've managed to not read this book until now. It was first published in 1999, and it's so my favourite kind of writing - quirky, unexpected, elegant and real. Anyway, it's taken me until this week to read it, and it's been one of those periods of synchronicity that occur sometimes, when enough random factors come together that result in something actually happening. The movie - which, like the book, I missed in the cinema, was on TV here just recently. I was actually watching the second State of Origin match with Dearly Beloved that night - an annual interstate battle of rugby league between new South Wales and Queensland, for my international readers - but a mate interstate had that choice superseded by his partner, I believe and they were watching Chocolat! Then, my very best friend in the world suddenly said something quite apropos of nothing, and this book came up... Also, the latest in what has now become a series of three books has just been released here. I figured it was time.

This is - pardon the pun - the most delicious book. Really! There is the most marvelous whimsy that underscores the narrative that is just so refreshing without being contrived at all. At the same time, there are some great truths, some very human truths, that are woven into the plot that make this such a solid read in many ways. There is great wisdom in Harris' writing, in the finely drawn characters, in her observance of human frailties and vulnerabilities. Given a choice, I would go out as Armande does, with her faculties, if not her body, intact and making a choice that is hers and hers alone to make. Given the choice, I would also live as Vianne does, totally on her own terms, in full acceptance of her difference. Although, the inner conflicts that she struggles with are no different, in reality, than the inner conflicts any of us have, if we're honest, that come with the life choices we make, as nothing is as simple as we'd like it to be.

Page 41 of my edition turned this up:

The hidden but simmering prejudices in the little village of Lansquenet-sous-Tannes are typical of most small communities. Fear of the outsider, condemnation of difference, ostracism of those who do not conform to local custom, fear of local authorities - in this case, the priest, Monsieur le cure, Francis Reynaud, a local boy with a past that he likes to believe has been erased by his long absence from the village...

Vianne and her daughter, Anouk, arrive on the wind on Shrove Tuesday, the beginning of Lent, and open a chocolaterie. It is a great affront to those who curry favour with the priest, who has a stranglehold over many of the villagers. Yet, the simplicity of Vianne's welcome, and her lack of adversarial characteristics endear her to many very quickly. Her warmth snowballs, extending to the river gypsies who land on the river bank below the village's tiny slum district, in the face of the villagers' animosity and outright hostility from the priest - whose hidden agenda colours his reaction to them.

There is humour, drama and tragedy within this story. However, the real tragedy is voiced by Anouk - out of the mouths of babes...

I haven't done an outline of the plot. I think I intended to, but it didn't happen. I wrote as the book itself led me to write, so this can't be properly called a review. I'm not sure what it is. If you've not read this lovely book, I strongly recommend it. If you've not seen the film, get that too. The version with Juliette Binoche, Johnny Depp and Judi Dench is faithful to the text for the most part, although there are amalgamations and contractions of characters. That doesn't detract though - and I don't think there's any reason to get rabid about reading it first then seeing the film or vice versa. I saw the film first and have loved the book. I don't know that loving the book first is going to detract from what is a lovely film in its own right.

I've started The Lollipop Shoes, the next in the series... I'll be back with more when I've finished that!

This is - pardon the pun - the most delicious book. Really! There is the most marvelous whimsy that underscores the narrative that is just so refreshing without being contrived at all. At the same time, there are some great truths, some very human truths, that are woven into the plot that make this such a solid read in many ways. There is great wisdom in Harris' writing, in the finely drawn characters, in her observance of human frailties and vulnerabilities. Given a choice, I would go out as Armande does, with her faculties, if not her body, intact and making a choice that is hers and hers alone to make. Given the choice, I would also live as Vianne does, totally on her own terms, in full acceptance of her difference. Although, the inner conflicts that she struggles with are no different, in reality, than the inner conflicts any of us have, if we're honest, that come with the life choices we make, as nothing is as simple as we'd like it to be.

Page 41 of my edition turned this up:

... In my profession it is a truth quickly learned that the process of giving is without limits. Guillaume left La Praline with a small bag of florentines in his pocket; before he had turned the corner of Avenue des Francs Bourgeois I saw him stoop to offer one to the dog. A pat, a bark, a wagging of the short stubby tail. As I said, some people ever have to think about giving.While Vianne frames this concept within the bounds of her profession as a chocolatier, it has a wider application. Within my own tradition it is a mitzvah to give. The Hebrew word translates variously, sometimes used as 'good deed', but in essence it is a law. The 613 mitzvot are the 613 commandments that make up halachah, Jewish Law. We are commanded to give. Not indiscriminately. We are commanded to give within our means, as to give more than we can afford means we could ourselves become a burden for someone else, and that is contrary to the law. Vianne's gifts allow her to see past people's facades to their inner longings, enabling her to offer the chocolates that are their favourites - even though they might not know that themselves. In opening them to the satisfaction of those inner longings, she unlocks many of their constraints - things that bind them as individuals and as they relate to others.

The hidden but simmering prejudices in the little village of Lansquenet-sous-Tannes are typical of most small communities. Fear of the outsider, condemnation of difference, ostracism of those who do not conform to local custom, fear of local authorities - in this case, the priest, Monsieur le cure, Francis Reynaud, a local boy with a past that he likes to believe has been erased by his long absence from the village...

Vianne and her daughter, Anouk, arrive on the wind on Shrove Tuesday, the beginning of Lent, and open a chocolaterie. It is a great affront to those who curry favour with the priest, who has a stranglehold over many of the villagers. Yet, the simplicity of Vianne's welcome, and her lack of adversarial characteristics endear her to many very quickly. Her warmth snowballs, extending to the river gypsies who land on the river bank below the village's tiny slum district, in the face of the villagers' animosity and outright hostility from the priest - whose hidden agenda colours his reaction to them.

There is humour, drama and tragedy within this story. However, the real tragedy is voiced by Anouk - out of the mouths of babes...

"Are we staying? Are we, Maman?" She tugs at my arm, insistently. "I like it, I like it here. Are we staying?"

I catch her up into my arms and kiss the top of her head. She smells of smoke and frying pancakes and warm bedclothes on a winter's morning.

Why not? It's as good a place as any.

"Yes, of course," I tell her, my mouth in her hair. "Of course we are."

Not quite a lie. This time it may even be true.Anouk has all the characteristics of a gypsy child - resilience, strength of character, acceptance of her lot, wisdom beyond her years, precocious insight, and the ability to land in a place become part of it quickly - just as Vianne had as the child of a wandering, 'different' mother. Yet, she yearns for stability, she yearns to stay in a place long enough to keep the friends she makes, she yearns to fit in. Vianne senses this in her, wants to give it to her, and yet can't erase her own ghosts sufficiently to grant her this wish. As always, when a certain wind blows, the restlessness starts to pick at her, her sense of having achieved all she can in a place becomes more than she can resist.

I haven't done an outline of the plot. I think I intended to, but it didn't happen. I wrote as the book itself led me to write, so this can't be properly called a review. I'm not sure what it is. If you've not read this lovely book, I strongly recommend it. If you've not seen the film, get that too. The version with Juliette Binoche, Johnny Depp and Judi Dench is faithful to the text for the most part, although there are amalgamations and contractions of characters. That doesn't detract though - and I don't think there's any reason to get rabid about reading it first then seeing the film or vice versa. I saw the film first and have loved the book. I don't know that loving the book first is going to detract from what is a lovely film in its own right.

I've started The Lollipop Shoes, the next in the series... I'll be back with more when I've finished that!

Monday 18 June 2012

Book junkie drugs

Fellow book junkies, we maybe need to roll this out on posters, t-shirts, mugs...what do you think?

Meantime - I'm on a success roll. I will be watching the letter box like a hawk - I found a copy of John Wyndham's Seeds of Time on Ebay! Yay!! WAY cheaper than the collectors edition on Amazon for the mere sum of $250...which I thought, given the excesses of the past few weeks, was perhaps not somewhere I should go!

I also reached a milestone overnight. I started this blog back in January, and last night rolled over 2000 hits. Thank you to everyone who is reading me. Thank you for all your comments. This is one of the most fun things I've done in ages, and a big part of it is the voices that you all contribute to the discussions. For those of you lurking on the fringes, don't be shy - sign up and follow, and have your say.

Meantime - I'm on a success roll. I will be watching the letter box like a hawk - I found a copy of John Wyndham's Seeds of Time on Ebay! Yay!! WAY cheaper than the collectors edition on Amazon for the mere sum of $250...which I thought, given the excesses of the past few weeks, was perhaps not somewhere I should go!

I also reached a milestone overnight. I started this blog back in January, and last night rolled over 2000 hits. Thank you to everyone who is reading me. Thank you for all your comments. This is one of the most fun things I've done in ages, and a big part of it is the voices that you all contribute to the discussions. For those of you lurking on the fringes, don't be shy - sign up and follow, and have your say.

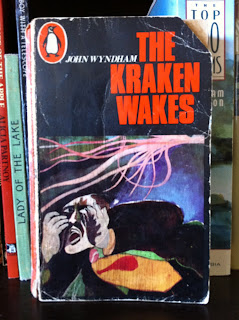

The Kraken Wakes - John Wyndham

The Kraken Wakes is one of John Wyndham's early novels, first published in 1953. In some ways, it is almost a template for many of his other books. There are things that some of the later books have in common - a business-like narrator with an insightful partner, a global perspective on the long-term ramifications of the problem that forms the core of the story, well-drawn believable characters, and a style of story telling that creeps in and insinuates a possibility that what we are reading is, perhaps, not entirely fiction - it could be real...

My copy is, like most of my Wyndhams, an early 60s Penguin paperback with an almost Munch-like illustration on the cover. It's too much like The Scream for John Byrne, the artist, not to have been referencing him.

I tend not to re-read this one as often as some of Wyndham's other books. I'm not sure why, because when I do, I find myself captivated. This time around, a number of different things surfaced for me - as is often the case - but some of the parallels and anticipations of things to come, juxtaposed together in the one story, were quite startling and I'm not sure why I never noticed them within that frame of reference before.

This is another of Wyndham's masterful stories of extra-terrestrial invasion, only this time it actually happens. There is alien technology, but there are subtleties that could only be Wyndham's - no flashy firepower or forceful overpowering of the planet. UFOs certainly - which are the first warning, but UFOs that appear in the form of clusters of mysterious red, fuzzy spheres which appear and then vanish beneath the surface of the ocean. A few military types have a go at them with traditional weaponry, both air and sea-borne. Mike and Phyllis, by chance, are witnesses to one of the earliest sightings while on a cruise for their honeymoon. As journalists for the EBC (English Broadcasting Commission), they are able to convince the captain of the ship to share with them his official report as well as getting him to divulge information about other sightings. They file a report that is broadcast back in England, but like others elsewhere, partly due to the fact that beyond the curiosity factor nothing else seems to happen, the story fizzles and dies.

Some time later, scientific reports start to emerge about deep sea silting appearing at unprecedented shallow depths. Another curiosity, which fails to gain much momentum. Then ships mysteriously start to go down, eventually halting all but coastal seafaring. However, it isn't until the first attacks on people that any notice begins to be paid, and even then, the locations are remote, and it remains a tragic, but smallish story. Enter Alistair Bocker, scientist of some notoriety and rapidly gaining a reputation as a sensationalist and crank, as he comes forward with wildly extreme explanatory theories and predictions. He sponsors a trip to the location where he predicts the next attack will be, taking with him a press corps, including Mike and Phyllis. They get their story; Bocker was right in his location, but wholly unprepared for the risks involved, and four of their team are lost, along with a large percentage of the local population. Arising from the sea in the depths of the night, huge 'sea tanks', featureless metal vehicles, make their way into the square of the seaside town and explode sticky tentacle-like filaments which take hold of their powerless victims, pulling them in back into the ocean. Phyllis is only saved when one of the filaments snakes through the window of their room but Mike manages to hold on long enough for her skin to tear away, freeing her.

In due course, these attacks increase around the world and the authorities begin to find ways to defend themselves. New technology in depth charges also allows for bombing in the deeps, where it is known the invaders lurk, and for a while things calm down. Until the sea levels start to rise. And rise... Again, Bocker leads the way, predicting that this is the beginning of the end game. Again, he is dismissed. Once again, he is right - sea temperatures are warmed in the Arctic and Antarctic and the great glaciers start to calve, currents driving the icebergs towards the equator, melting and bringing more and more water advancing on the land. Inevitably, as the waters rise, communities that are already in crisis in the wake of the ceasing of sea freight due to the dangers to shipping begin to break down into anarchy. The English government, relocated to higher ground in Yorkshire goes silent suddenly as their enclave is over taken by those on the outside who believe they are holding out. At this point, Mike and Phyllis decide the time has come to leave the EBC stronghold in London and risk the perilous journey to their cottage on high ground in Cornwall - which, as Mike discovers on arrival, Phyllis has secretly fortified and equipped with supplies to last a long time.

Structurally, the book introduces us to the story in hindsight with a brief preface where the narrator, Mike Watson, discusses their present isolated, post-disaster situation with his wife Phyllis, and says that he'll write about what happened. That, while there will be numerous official documentations and histories of events created, as someone who was there from the beginning, he has a particular take on it and that a more personal account will have a different value than the 'official' versions. It then moves straight into a chronological narrative that is broken into three phases. Each has its own flavour, but all are marked by tones of increasing desperation as it becomes obvious that the human population is engaged in mortal combat with an enemy that they can't physically identify, can't engage with directly, and can't take on on any level playing field.

In the very beginning of Phase One, while Mike is still setting the scene, there are a couple of paragraphs that I have read so many times in my multiple readings of this book, but this time they really grabbed my attention.

This is an all too human tendency. We are, most of us, innately optimistic. We try hard to put a good face on things even in the worst of circumstances. If you consider that this was published less than ten years after the end of World War II, Wyndham's war experiences must have been still very fresh in his mind, and he and the rest of the world would still have been struggling to come to terms with the horrors of the eleven million dead at the hands of Hitler's campaign of hate - six million Jews and five million others.

The other, more contemporary connection that emerged for me was the parallel between the eco-war waged by the invaders in Wyndham's book and what we are watching happen to the planet now as a result of our own industrial excesses coupled with the evolution of planetary change. In this case, there's a spooky visionary-ness on Wyndham's part, which is by no means unique to this book. The Maldives are disappearing - these tiny islands have been an off-beat tourist destination for a long time. White, white sand, crystal clear ocean, a pristine environment and a fascinating local population attract people year round. However, rising sea levels are a real threat to this tiny nation, and already, calls are going out to other countries for refuge when, eventually they go under. The high ground will become prized, as it did in the novel. The struggle for survival in the face of the encroaching waters, when whole societies imploded, turning on each other, can be seen as a warning for us now. What do we need to do to plan for a future where the world, already over-populated and with dwindling resources, could be very different?

At the end of the book, Mike and Phyllis are recalled to London as rebuilding begins once the water level stabilises. The world population is some fifth to an eighth smaller than it was, but ultrasound technology has helped defeat the invaders. Phyllis has the last word,

My copy is, like most of my Wyndhams, an early 60s Penguin paperback with an almost Munch-like illustration on the cover. It's too much like The Scream for John Byrne, the artist, not to have been referencing him.

I tend not to re-read this one as often as some of Wyndham's other books. I'm not sure why, because when I do, I find myself captivated. This time around, a number of different things surfaced for me - as is often the case - but some of the parallels and anticipations of things to come, juxtaposed together in the one story, were quite startling and I'm not sure why I never noticed them within that frame of reference before.

This is another of Wyndham's masterful stories of extra-terrestrial invasion, only this time it actually happens. There is alien technology, but there are subtleties that could only be Wyndham's - no flashy firepower or forceful overpowering of the planet. UFOs certainly - which are the first warning, but UFOs that appear in the form of clusters of mysterious red, fuzzy spheres which appear and then vanish beneath the surface of the ocean. A few military types have a go at them with traditional weaponry, both air and sea-borne. Mike and Phyllis, by chance, are witnesses to one of the earliest sightings while on a cruise for their honeymoon. As journalists for the EBC (English Broadcasting Commission), they are able to convince the captain of the ship to share with them his official report as well as getting him to divulge information about other sightings. They file a report that is broadcast back in England, but like others elsewhere, partly due to the fact that beyond the curiosity factor nothing else seems to happen, the story fizzles and dies.

Some time later, scientific reports start to emerge about deep sea silting appearing at unprecedented shallow depths. Another curiosity, which fails to gain much momentum. Then ships mysteriously start to go down, eventually halting all but coastal seafaring. However, it isn't until the first attacks on people that any notice begins to be paid, and even then, the locations are remote, and it remains a tragic, but smallish story. Enter Alistair Bocker, scientist of some notoriety and rapidly gaining a reputation as a sensationalist and crank, as he comes forward with wildly extreme explanatory theories and predictions. He sponsors a trip to the location where he predicts the next attack will be, taking with him a press corps, including Mike and Phyllis. They get their story; Bocker was right in his location, but wholly unprepared for the risks involved, and four of their team are lost, along with a large percentage of the local population. Arising from the sea in the depths of the night, huge 'sea tanks', featureless metal vehicles, make their way into the square of the seaside town and explode sticky tentacle-like filaments which take hold of their powerless victims, pulling them in back into the ocean. Phyllis is only saved when one of the filaments snakes through the window of their room but Mike manages to hold on long enough for her skin to tear away, freeing her.

In due course, these attacks increase around the world and the authorities begin to find ways to defend themselves. New technology in depth charges also allows for bombing in the deeps, where it is known the invaders lurk, and for a while things calm down. Until the sea levels start to rise. And rise... Again, Bocker leads the way, predicting that this is the beginning of the end game. Again, he is dismissed. Once again, he is right - sea temperatures are warmed in the Arctic and Antarctic and the great glaciers start to calve, currents driving the icebergs towards the equator, melting and bringing more and more water advancing on the land. Inevitably, as the waters rise, communities that are already in crisis in the wake of the ceasing of sea freight due to the dangers to shipping begin to break down into anarchy. The English government, relocated to higher ground in Yorkshire goes silent suddenly as their enclave is over taken by those on the outside who believe they are holding out. At this point, Mike and Phyllis decide the time has come to leave the EBC stronghold in London and risk the perilous journey to their cottage on high ground in Cornwall - which, as Mike discovers on arrival, Phyllis has secretly fortified and equipped with supplies to last a long time.